Transformational thought from Bill Walsh’s book, The Score Takes Care of Itself:

Culture is everything to a organization or a team or a family.

And acting like you are who you want to be is powerful magic.

Transformational thought from Bill Walsh’s book, The Score Takes Care of Itself:

Culture is everything to a organization or a team or a family.

And acting like you are who you want to be is powerful magic.

Ryan Holiday had this book on his recommended reading list, and I was intrigued enough to put it on my holiday wish list.

Bill Walsh was the cerebral, stoic coach who created the San Francisco 49ers football dynasty. He wasn’t known for sideline bluster or emotional outbursts. He was John Wooden-esque in his sage-like approach to leading his team as well as in his remarkable success.

He set an expectation of excellence within the whole organization, from the receptionists to the star quarterback. And he didn’t put his focus or his team’s on anything out of their control. Do your absolute best in this moment, repeat that approach continually, and “the score will take care of itself.”

This approach just makes sense. Focus on systems, not goals. Refine the process that brings out your best, and let the results take care of themselves. Don’t get attached to outcomes.

I’ve just started reading and can already tell that there is a lot of wisdom here. Walsh, whose public persona was one of the complete calm and control, begins the book with a story about his second season coaching the 49ers and his emotional collapse after losing yet another game in a disappointing season. He cried uncrontollably on a cross-country flight with his team after losing a heart-breaking game in Miami, with his assistant coaches shielding him at the front of the plane to keep the players from seeing him in such a state. His response to that emotional breakdown led the way to his first Super Bowl title the very next season.

I didn’t expect Bill Walsh to open the book with such vulnerability, and that let me know this was not just another superficial leadership pep talk from an ex-coach.

I’m looking forward to gleaning some wisdom from this book that I can take back to my team and be a better resource and leader for those I serve.

There’s been something missing from my life lately.

Fiction.

My reading has been sporadic and mostly non-fiction over the last couple of months.

My wife and I haven’t even made time for television or movies.

And I can feel that something is off.

Maybe we need regular doses of story and mental escape. Too much reality (and online news and social media especially) dulls the imagination. All work and no play is not a good recipe for a creative mind.

Regular doses of fiction stoke the imagination and spark more wonder and delight.

So, after seeing it mentioned again by Jason Snell, I’m giving this well-reviewed science fiction series a go.

On my long drive yesterday I listened again to one of my favorite audiobooks, Steve Martin’s Born Standing Up.

When Martin was describing his teen years, he mentioned this conversation with an older coworker in his job at Disneyland:

“One day I was particularly gloomy, and Jim asked me what the matter was. I told him my high school girlfriend (for all of two weeks) had broken up with me. He said, ‘Oh, that’ll happen a lot.’ The knowledge that this horrid grief was simply a part of life’s routine cheered me up almost instantly.” –Steve Martin, from his book Born Standing Up

I remember being crushed by teenage heartbreak. It lingered like a cloud over me for way too long.

If only I had a Jim to tell me it was no big deal; heartbreaks are part of life; they’ll happen a lot.

Maybe I would have cheered up a lot quicker. (Or maybe not.)

Now, I regularly have young people seek my counsel about the uncertainties in their lives. “What path should I take?” “Why don’t I have answers to my hard questions?”

I want to tell them—and sometimes I do—”You will never be certain. Ever.”

That sentiment should be reassuring, right? If you don’t have it figured out, don’t fret because you never will. This horrid confusion is simply part of life’s routine.

I’m 51-years-old, and I am not close to having my life figured out. I’m totally winging it. (You are, too.)

I used to think there would come a point in my life when I would have “arrived”, when I would be sure and supremely confident and oh so wise.

Now I’m sure that point is perpetually receding into the horizon of my life.

I look at people two or three decades older than me and see just as much uncertainty.

Quarter-life crisis. Mid-life crisis. Late-life crisis.

You will face a lot fewer crises if you’re not expecting that your life will eventually resolve into blissful certitude.

The secret to happiness is low expectations, or at least realistic expectations. Expect heartbreak and uncertainty and loss and failure, and when you encounter them they won’t seem so dismal.

This is not pessimism. This is honesty. This is steeling yourself to meet life head on and make the most of whatever comes. And heartbreak and loss and uncertainty are coming.

But so is joy and delight and kindness and opportunities to grow and embrace all that your unscripted shot at life has to offer.

Step back and see that whatever gloom you’re facing is merely temporary. Everything is temporary. This is life’s routine, and you get to be a part of it. How grand.

Cheer up and get back at it.

I spent more than five hours in the car tonight, driving to a family beach getaway for this holiday weekend.

My wife and I listened to the audiobook of Amy Poehler’s Yes Please.

It doesn’t seem to have much of a narrative arc, but it’s a fun listen. Poehler narrates herself and there are surprise guest voices who add serendipitous fun.

She is candid and occasionally crude, but she is endearing throughout with thoughtful insights and doses of life wisdom. And now I just want to binge watch Parks and Recreation.

By the way, the gold standard of comedy memoir audiobooks is Steve Martin’s Born Standing Up. So, so good.

Daniel Coyle’s book, The Talent Code, is one of the best books I’ve read in the last couple of years. He explores “talent hotbeds”, places that produce a disproportionate amount of talented people in various fields—sports, the arts, and academics. And he comes up with key factors that separate the best from all others.

His follow-up book, The Little Book of Talent, condenses the lessons he learned about talent into very direct, transferable and applicable insights.

And this is the key insight:

“If I had to sum up the difference between people in the talent hotbeds and people everywhere else in one sentence, it would be this:

People in the hotbeds have a different

relationship with practicing.

Many of us view practice as necessary drudgery, the equivalent of being forced to eat your vegetables, far less important or interesting than the big game or the big performance. But in the talent hotbeds I visited, practice was the big game, the center of their world, the main focus of their daily lives. This approach succeeds because over time, practice is transformative, if it’s the right kind of practice. Deep practice.

The key to deep practice is to reach. This means to stretch yourself slightly beyond your current ability, spending time in the zone of difficulty called the sweet spot. It means embracing the power of repetition, so the action becomes fast and automatic. It means creating a practice space that enables you to reach and repeat, stay engaged, and improve your skills over time.”

Everything changes when you see practice as not just a means to an end, but a worthy end in itself.

This applies to all of life, actually. Every moment is a chance to practice intention and focus and mindfulness.

Practice, then, is not merely preparation for something else, but is rather the act of honoring the only place your life ever is—here and now.

From Susan Cain’s book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, there’s this excerpt from the memoir of Steve Wozniak, the quieter and lesser known of the two Steves who founded Apple:

“Most inventors and engineers I’ve met are like me—they’re shy and they live in their heads. They’re almost like artists. In fact, the very best of them are artists. And artists work best alone where they can control an invention’s design without a lot of other people designing it for marketing or some other committee. I don’t believe anything really revolutionary has been invented by committee. If you’re that rare engineer who’s an inventor and also an artist, I’m going to give you some advice that might be hard to take. That advice is: Work alone. You’re going to be best able to design revolutionary products and features if you’re working on your own. Not on a committee. Not on a team.”

I do think that group work is overrated. Group brainstorming, even, has been shown to actually come up with fewer ideas than when individuals work on idea generation alone.

A team possibly can improve your ideas and offer feedback and new possibilities and enact plans to execute ideas, but the fundamental work is likely done on your own, in your zone.

I’m currently reading Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. It’s making me realize my personality is a fairly even split of introversion and extroversion; I suppose that makes me an “ambivert”, and I’m sure most people are more split than they assume.

Most people who know me wouldn’t hesitate to label me an extrovert. I’m sure I come across publicly as gregarious and not at all spotlight-averse.

But I prefer alone time over group time. A great lunch for me is lunch by myself with something good to read. I tend to choose staying in over going out and one-on-one conversation rather than a dinner party with a crowd. But if I’m at a dinner party, I can, if I choose, be engaging and even entertaining. (I’m hilarious, right friends?) I don’t enjoy small talk, but I can hold my own

My two primary peak experiences when I work, though, are seemingly at opposite ends of the personality spectrum.

I fall into a sort of creative bliss when working alone and getting into a flow state where I lose track of time and ideas appear and possibilities bubble up.

But I get a different kind of high that’s just as satisfying when I stand on a stage and connect with an audience, often about the ideas that came about in that isolated flow state. That peak on-stage experience is also a flow state.

I’m most creative alone after having some time to get into a zone. I’m most alive when I’m in front of an audience sharing what I crafted in that alone time.

I had a colleague in my first career when I was a staff member on Capitol Hill who regularly wanted to pull up a chair next to me so we could write together. That did not work. And I finally told him just to send me his ideas, and I would synthesize them on my own.

I’ve learned to structure my time around what works best for me. I don’t seek out lunch appointments or group work. I make sure to get plenty of down time before and after presentations. I value long stretches of quiet time.

Know yourself. Look back on your peak moments, your most productive environments, and your most satisfying states. Determine how best to bolster your strengths and hack your personality to more completely fulfill your nature.

I was browsing in a local independent book shop with my daughter today. The serendipity of discovery in a book shop has an organic vitality to it that Amazon’s algorithms just can’t match.

The staff had placed copies of famed Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami’s newest release, Wind/Pinball: Two Novels (which, actually, were his first two novels), on a front table, and I opened it to the introduction and read this remarkable story of how his writing career began:

One bright April afternoon in 1978, I attended a baseball game at Jingu Stadium, not far from where I lived and worked. It was the Central League season opener, first pitch at one o’clock, the Yakult Swallows against the Hiroshima Carp. I was already a Swallows fan in those days, so I sometimes popped in to catch a game—a substitute, as it were, for taking a walk.

Back then, the Swallows were a perennially weak team (you might guess as much from their name) with little money and no flashy big-name players. Naturally, they weren’t very popular. Season opener it may have been, but only a few fans were sitting beyond the outfield fence. I stretched out with a beer to watch the game. At the time there were no bleacher seats out there, just a grassy slope. The sky was a sparkling blue, the draft beer as cold as could be, and the ball strikingly white against the green field, the first green I had seen in a long while. The Swallows first batter was Dave Hilton, a skinny newcomer from the States and a complete unknown. He batted in the leadoff position. The cleanup hitter was Charlie Manuel, who later became famous as the manager of the Cleveland Indians and the Philadelphia Phillies. Then, though, he was a real stud, a slugger the Japanese fans had dubbed “the Red Demon.”

I think Hiroshima’s starting pitcher that day was Yoshiro Sotokoba. Yakult countered with Takeshi Yasuda. In the bottom of the first inning, Hilton slammed Sotokoba’s first pitch into left field for a clean double. The satisfying crack when the bat met the ball resounded throughout Jingu Stadium. Scattered applause rose around me. In that instant, for no reason and on no grounds whatsoever, the thought suddenly struck me: I think I can write a novel.

I can still recall the exact sensation. It felt as if something had come fluttering down from the sky, and I had caught it cleanly in my hands. I had no idea why it had chanced to fall into my grasp. I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now. Whatever the reason, it had taken place. It was like a revelation. Or maybe epiphany is the closest word. All I can say is that my life was drastically and permanently altered in that instant—when Dave Hilton belted that beautiful, ringing double at Jingu Stadium.

He then went home and began writing his first novel, thus beginning a distinguished career as one of the most significant writers of the generation.

What an odd way to have a career epiphany. Maybe I’ve had similar moments where my attention was on one thing and an insight from elsewhere struck me.

But Murakami’s story is remarkable because the next morning he arose early and started writing. And he kept at it over many months until he had written his first novel. That first attempt ended up winning a writing prize and made him into a full-time author.

The Dave Hilton double and its resulting epiphany wouldn’t amount to much of a story if Murakami hadn’t taken action, if he hadn’t begun doing what novelists do.

And that’s the real lesson for me. Don’t hope for a light-bulb moment (or a lead-off double moment). Just decide what gift you want to share and get busy doing something about it.

Act as if you are who you want to be and do what that person would do.

I’m on a big picture, big history kick right now.

I’ve been reading a great history of Homo sapiens, and I’ve started listening to the audio version of Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything.

Bryson’s book is a delightful survey of the biggest ideas and discoveries that explain what we know about the universe.

What stands out is just how much we got wrong and how certain we were in our errors.

The steps forward were usually dependent on those who were willing to embrace uncertainty and not-knowing, who could follow their curiosity rather than their egos.

Richard Dawkins from his book, Unweaving The Rainbow:

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Arabia. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively exceeds the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.”

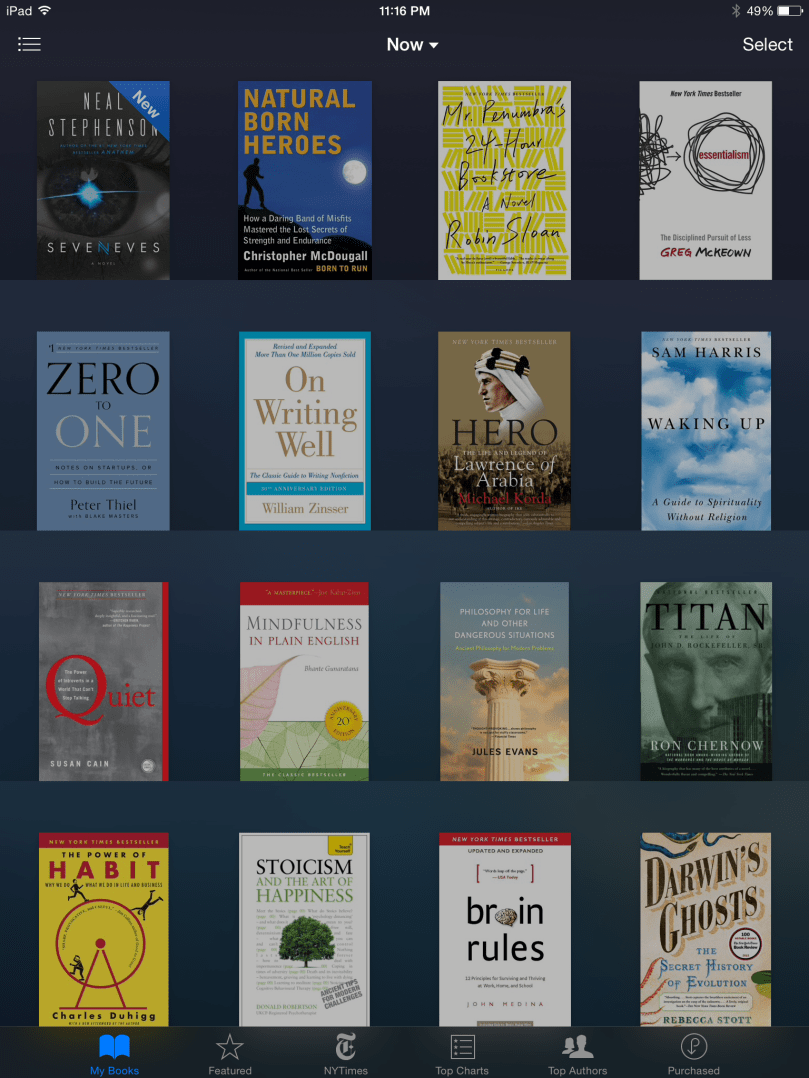

I typically have at least two books or more in play at any time. Right now it’s Sapiens, a “history of humankind”, and the sci-fi novel Seveneves by Neal Stephenson.

But I can’t resist adding to my reading list. E-books make it easy to try samples of books before buying.

Here’s what’s on my to-consider-next list for books:

Philosophy, a memoir, historical fiction, something about training a hawk, what appears to be THE definitive account of The Beatles, and an epic biography.

It’s a delight to ponder what might be next in capturing my attention and inspiring new thoughts and different ways of understanding.

Keep your reading fresh and varied. And just keep reading.

Remember, Meditations was written by Marcus Aurelius as a sort of ongoing “note to self” while he was the Roman emperor, essentially the most powerful and influential person in the western world at the time.

He’s not lecturing someone else. He’s exhorting himself, calling for his own best, reminding himself of the kind of man he aspired to be. He could have gotten away with murder, much less selfish and boorish behavior.

Which makes passages like this (3.5) so remarkable:

“How to act:

Never under compulsion, out of selfishness, without forethought, with misgivings.

Don’t gussy up your thoughts.

No surplus words or unnecessary actions.

Let the spirit in you represent a man, an adult, a citizen, a Roman, a ruler. Taking up his post like a soldier and patiently awaiting his recall from life. Needing no oath or witness.

Cheerfulness. Without requiring other people’s help. Or serenity supplied by others.

To stand up straight—not straightened.”

From Sam Harris’s book, Waking Up:

“The Buddha taught mindfulness as the appropriate response to the truth of dukkha, usually translated from the Pali, somewhat misleadingly, as ‘suffering.’ A better translation would be ‘unsatisfactoriness.’ Suffering may not be inherent in life, but unsatisfactoriness is. We crave lasting happiness in the midst of change: Our bodies age, cherished objects break, pleasures fade, relationships fail. Our attachment to the good things in life and our aversion to the bad amount to a denial of these realities, and this inevitably leads to feelings of dissatisfaction. Mindfulness is a technique for achieving equanimity amid the flux, allowing us to simply be aware of the quality of experience in each moment, whether pleasant or unpleasant. This may seem like a recipe for apathy, but it needn’t be. It is actually possible to be mindful—and, therefore, to be at peace with the present moment—even while working to change the world for the better.”

A passage from the book, Sapiens, contrasting the lives of our hunter-gatherer ancestors with the consequences of the Agricultural Revolution:

“Foragers knew the secrets of nature long before the Agricultural Revolution, since their survival depended on an intimate knowledge of the animals they hunted and the plants they gathered. Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more difficult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud.”

Fascinating. This book is filled with insights about the human experience and how we’ve come to be where we are now.

Author Neil Gaiman from his lecture on the power of books and libraries:

I was in China in 2007, at the first party-approved science fiction and fantasy convention in Chinese history. And at one point I took a top official aside and asked him Why? SF had been disapproved of for a long time. What had changed?

It’s simple, he told me. The Chinese were brilliant at making things if other people brought them the plans. But they did not innovate and they did not invent. They did not imagine. So they sent a delegation to the US, to Apple, to Microsoft, to Google, and they asked the people there who were inventing the future about themselves. And they found that all of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. Discontent is a good thing: discontented people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different.

And he closes with this reference to Einstein:

Albert Einstein was asked once how we could make our children intelligent. His reply was both simple and wise. “If you want your children to be intelligent,” he said, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” He understood the value of reading, and of imagining. I hope we can give our children a world in which they will read, and be read to, and imagine, and understand.

I’ve started two new books this week – Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari and Seveneves, a new novel by Neal Stephenson.

I like to balance non-fiction and fiction, usually reading a novel at night and the non-fiction earlier in the day. Non-fiction tends to spark ideas, and I don’t need that right before going to sleep.

These two new books I’m reading make for a particularly interesting balance of ideas. Sapiens is a surprisingly readable and fascinating history of the origins of our species. While Seveneves is a novel about the near future and the end of the world as we know it and how humans adapt and persist through a cataclysm.

I’m appreciating even more what good fortune it is to be a human on this planet in this time. The triumph of our species was not inevitable, and there’s no guarantee we are not going to screw things up epically.

On a cosmic scale our time in the sun has been incredibly brief. Dinosaurs roamed the earth significantly longer than we have so far.

Knowing where we came from can make us better appreciate what we have now and just where we might go from here.

The author William Zinsser died recently, and his obituary in the New York Times prompted me to start reading his highly acclaimed book, On Writing Well. The book had been recommended by several writers I respect, including John Gruber of my favorite Apple web site, Daring Fireball.

The book begins with a firm exhortation to simplify:

“Look for the clutter in your writing and prune it ruthlessly. Be grateful for everything you can throw away. Reexamine each sentence you put on paper. Is every word doing new work? Can any thought be expressed with more economy? Is anything pompous or pretentious or faddish? Are you hanging on to something useless just because you think it’s beautiful?

Simplify, simplify.”

I’m two chapters in to Zinsser’s book and already more aware of how sloppy my writing is. I just went back to the post I wrote yesterday and trimmed a few unnecessary words.

Writing should serve a purpose, and anything that detracts from that purpose should be eliminated. Simplify. Do less, better.

This is good advice for writing, but it applies well to living, too.

Consider the passage above with these changes:

“Look for the clutter in your life and prune it ruthlessly. Be grateful for everything you can throw away. Reexamine every thing (or commitment or relationship) you put in your life. Is every thing doing new (or meaningful) work? Can any task be done with more economy? Is anything pompous or pretentious or faddish? Are you hanging on to something (or someone) useless just because you think it’s (or he’s/she’s) beautiful?

Simplify, simplify.”

I’m currently switching between Natural Born Heroes and James Michener’s Hawaii.

Michener’s novel is such an epic, and I’m only 75 percent through it after weeks of light reading. But it holds up and keeps pulling me through it.

Next up in non-fiction after Natural Born Heroes will be Greg McKeown’s Essentialism. And my next novel will be Neal Stephenson’s latest, Seveneves, which just released tonight.

I continue to enjoy balancing non-fiction and fiction, usually saving the novel for night time reading and working through the non-fiction at lunch.

A crisp, bright, quiet spring Sunday morning.

A cup of tea (coconut) and Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations.

A Sunday morning ritual for me.

It’s hard to open this book without reading a passage that delights or challenges and refreshes my mind with its clarity and straightforward insight.

This passage today, 8.35:

“Don’t let your imagination be crushed by life as a whole. Don’t try to picture everything bad that could possibly happen. Stick with the situation at hand, and ask, “Why is this so unbearable? Why can’t I endure it?” You’ll be embarrassed to answer.

Then remind yourself that past and future have no power over you. Only the present—and even that can be minimized. Just mark off its limits. And if your mind tries to claim that it can’t hold out against that … well, then, heap shame upon it.”

Only the present.