I have an Abraham Lincoln problem. I’ve lost track of how many biographies on Lincoln I’ve read—this one more than once. I’ve got a bust of him on the window ledge by my office desk. He’s my automatic answer to the question “Who in history would you want to meet?” I have been in awe of him since I was a child in elementary school reading the little biography about him in our school library. And the more I learn about him, the more in awe I become. His intelligence and wit. His large-hearted wisdom and self-effacing humor and steely resolve. The effusive affection he engendered among those who got to know him well is telling. And, of course, he is the single most significant figure in the history of our nation, a nation that would not exist as it does now were it not for him.

Lincoln is a wonder, and that he appeared on the planet where and when he did is an excellent argument in favor of divine intervention in the affairs of men and nations.

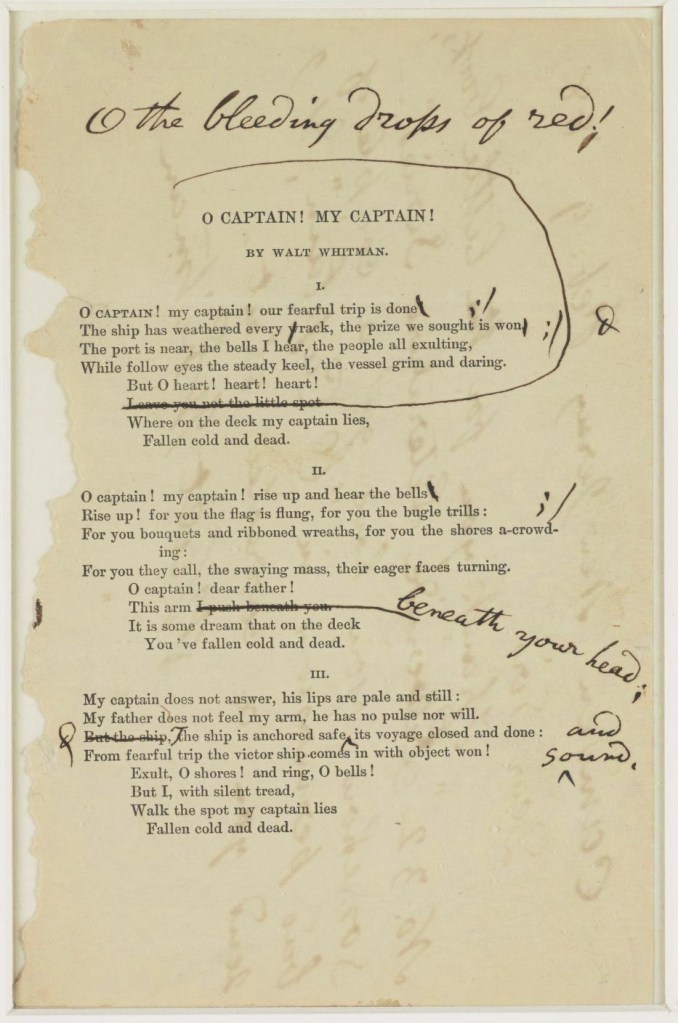

Today happens to be Lincoln’s birthday. (It’s also Charles Darwin’s birthday, and that two of the most remarkable men of the 19th century were born on the exact same day in 1809 is one of history’s most charming coincidences.) So, this month, in honor of Mr. Lincoln, I have chosen to learn by heart Walt Whitman’s tragic poem about Lincoln’s death. (His death, and its ill timing, set the nation back in a way we are still recovering from, so maybe an argument against divine intervention.)

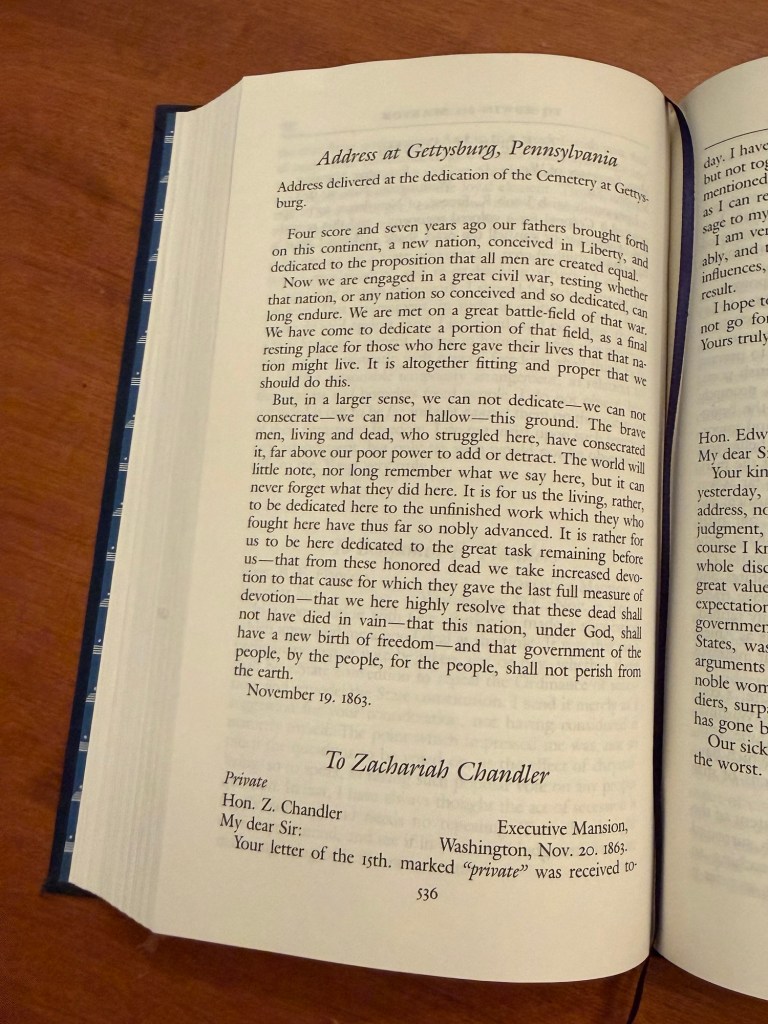

This poem is so sad. But, to balance out the pathos of that poem with something more positive, I’m also going to lock in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which, though not a poem, is a kind of civic art of the highest order. It is a jewel of simplicity and clarity and elegance reframing our national purpose.